P R A E S I D I U M

A Journal of Literate and Literary Analysis

6.1-2 (Winter/Spring 2006)

A quarterly publication of The Center for Literate Values

Board of Directors:

John R. Harris, Ph.D. (Executive Director)

Thomas F. Bertonneau, Ph.D. (Secretary)

Helen R. Andretta, Ph.D.; York College-CUNY

Ralph S. Carlson, Ph.D.; Azusa Pacific University

Kelly Ann Hampton

Michael H. Lythgoe, Lt. Col. USAF (Retd.)

"The Center’s immediate focus is on publishing, publicizing, and distributing books, pamphlets, and other printed material which furthers the revival of the Western tradition and, specifically, of tasteful literary art and morally responsible analysis. In keeping with its broad purpose, the Center is especially dedicated to representing an intellectually rich faith in the God of goodness and mercy to the academic community, and, equally and concurrently, exposing the community of believers to imaginative, challenging works of art. Our commitment to subtle artistic works of high caliber and substantial content is as firm as our commitment to well-reasoned apologetics and polemics: we seek to serve the cause of truth, not to propagandize." The Center for Literate Values, Objectives, sec. 2

View the previous issue of Praesidium (Fall 2005).

ISSN 1553-5436

© All contents of this journal (including poems, articles, fictional works, and short pieces by staff) are copyrighted by The Center for Literate Values of Tyler, Texas (2006), and may not be cited at length or reproduced without The Center's express permission.

*

Science fiction is the unintended but prominent theme of this edition, along with other more or less dire prophecies.

“I, Martian”: The Autoscopy of a Science Fiction Addict

Thomas F. Bertonneau

Professor Bertonneau explains that a paideia of science fiction prepares one for approaching creatively the challenges of terrestrial existence—a preparation sadly lacking among today’s young people.

The Narcissus Narcosis: A Platonic Dialogue on the Plight of Culture in Contemporary Society

John R. Harris

This send-up of Platonic style, wherein the shopping mall has replaced the agora, offers some far-from-frivolous solutions to our far-from-laughable problems.

Traditionalist Themes in Science Fiction and Fantasy

and

Science Fiction, Pop-Culture, and the World-Historical Crisis

Mark Wegierski

In two related pieces, Mr. Wegierski chronicles the role of science fiction in our popular culture over the past half-century and also wonders if this quintessentially “escapist” genre might not reveal something about our future, sometimes quite unconsciously.

Some Highly Impolitic Thoughts on Cultural Decay, Peasantry, and the Mexican Diaspora

Peter Singleton

Dr. Singleton dares to write what is declared in few other venues: that the real threat of Mexican immigration concerns class rather than race and pre-culture rather than alternative culture.

J. S. Moseby

This brief short story reminds us that whoever receives a child receives God.

Friedland, from Confessions of the Creature

Gary Inbinder

In an all-to-brief excerpt from a stunning historical novel (whose underpinning of fantasy is here invisible), we see Napoleon’s troops press the Russians into a frantic retreat.

*****

A Few Words from the Editor

I recently posed a group of college freshmen the question, “How might our society promptly and reasonably begin to reduce its ruinous dependency upon oil?” To my very great frustration, I found the group almost incapable of working beyond quite another question—that of how the price of gas at the pump might be wrested downward from the greedy clutches of self-interested industrialists and financiers. Most of these newly anointed voters could not see in life-by-petroleum any more consequential cost than that satisfied by the contents of their wallets. The conceptual failure here is itself part of the hidden cost, of course. That is, as we commit ourselves ever more rabidly to the post-literate life of speed and ease—a life wherein reading has become a chore and thought a violation of the right to be steadily amused—we must anticipate that our ability to grapple with generalities and abstractions will wither away. People, we must never forget, are almost infinitely malleable, particularly the young. If you have been reared in a trash dump, then you well know the various games offered by trash dumps, the various secrets, the various vistas: you become a connoisseur of trash dumps. There is no fact of human nature more daunting to the Platonist than this: i.e., that if human beings nurse deep within them a spark of the divine, they are also capable of feeding the infant flame litter rather than incense, and of growing rather fond of the resultant stench.

In blunt terms, this is lack of culture. Literacy, not spoken lore, is the means by which Western culture has been transmitted since (approximately) the time of Plato. The decline of literacy is therefore the death of culture and the birth, not of a new “manual orality” incited by clicks of the mouse or the remote channel stick, but of dull barbarism. I wanted to explore some of the situation’s ironies—and perhaps suggest a few ways of skirting the abyss—through my own salute to Platonic style, somewhat tongue-in-cheek but also deeply serious. My strange little contemporary dialogue, “The Narcissus Narcosis” (with its echo of Marshall McLuhan), was the result. Peter Singleton tackled some of the issues presently of great concern in this context more directly than I should have had the nerve to do. Indeed, his piece animated me to accelerate the present combined Winter/Spring edition, because I believe his remarks need to be read instantly. If ever there were an influence which an expiring literate culture did not need in its mortal struggle against intellectual torpor, it would surely be saturation in manual laborers wholly unfamiliar with the book, uninterested in correct expression, and hungry for the SUV and the wide-screen TV.

Whether or not we manage to preserve a few shreds of our moribund culture from Fast Food Alley and the speaking comic books which have become the movie industry, no sober optimist can suppose that our children’s children will not face a ravaged cultural landscape. Will that future be prowled by pitiless robots—or will human beings themselves have grown unrecognizable within a few decades? Remarkably, Tom Bertonneau and Mark Wegierski converged upon the subject of science fiction from two very different points of departure and quite without knowledge that the other was composing such a work for this issue. Dr. Bertonneau’s piece is nostalgic, for the most part, though he finishes in an inspiring indignation with those dull, earthbound hacks who may always be relied upon to keep any journey to the stars from achieving escape velocity. Mr. Wegierski’s inventory of the genre in film and literature is more occupied with how professedly idle visions of the future often extend certain political assumptions to their logical (and usually outlandish) conclusion. Together, these two works are not only wonderfully complementary: they also resonate with the issue’s broader question of just where our fishtailing culture will or can go from here.

I had thought, briefly, that I was in possession of three excellent fictional pieces for the first time in our journal’s history. One of the works was withdrawn, however, when its author apprehended that certain caustic portrayals of life on the university campus might prove career-damaging. The Brave New World of science fiction, apparently, is already on our doorstep. Look through that peephole before you burst forth to greet the day. ~J.H.

***************************

“I, Martian”: The Autoscopy of a Science Fiction Addict

by

Thomas F. Bertonneau

Dr. Thomas Bertonneau, a director on The Center’s board, is a faithful contributor to Praesidium. He currently teaches in the English Department at SUNY-Oswego The following essay intimates the origins of an enthusiasm which would produce his new book, The Gospel According to Sci-Fi (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2006), co-authored by Kim Paffenroth. The book is now on sale at Amazon.com.

[When I was ten years old in 1941, my] Uncle Frank presented me with a volume called The Marvels and Mysteries of Science… full of photographs of stars, waterfalls, and other interesting objects. One morning, lying in bed, I read the chapter on the planets, and learned Professor [Percival] Lowell ’s theory that Mars might be inhabited by a race who dig canals as straight as Roman roads. This seemed another one of those remarkable pieces of information that I should have been told at the age of five, and had for some reason been withheld from me. I began to read everything on astronomy I could find in the local library. – Colin Wilson, Voyage to a Beginning (1966)

It was 1961, and I was on a lecture tour of America – one of the exhausting series of daylong seminars and one-night stands that killed Dylan Thomas… In Ohio , I bought the Modern Library Giant of Science Fiction Stories, edited by Healy and McComas…. It had been many years – at least fourteen – since I had last read a science fiction story…. Now, suddenly, the taste came back; at the same time, I experienced an insight that struck me as revelatory. It seemed to me, quite simply, that science fiction was perhaps the most important form of literary creation that man had ever discovered. – Colin Wilson, Science Fiction as Existentialism (1978)

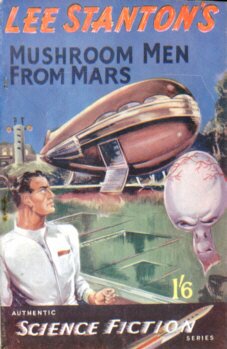

I

My romance with the supposedly popular – that is to say, vulgar – genre known as science fiction is altogether intertwined with my acquisition of literacy and self-awareness. So much indeed is this the case that I cannot write of all those magazines and books (printed on the cheapest and most perishable paper possible and with lurid cover-illustrations) without writing also of myself, of my infantile and adolescent milieux, and of the friends and relatives and acquaintances who impinged on me because they, too, had been lifted up from suburban insipidity into the higher sphere of planetary narrative. I write “supposedly popular” because, while science fiction used to have wide currency as a literary genre, it no longer does. Bookstores still have shelves dedicated to science fiction, so-called; but the books on those shelves correspond to a different genre from the one that entranced, informed, and edified me.

Like music, science fiction has occasionally delivered me from melancholy and dissipation, as it did, weirdly, in the dog days of my first foray into undergraduate matriculation at UCLA in the early 1970s. I shall come to that. Seeing, handling, smelling a vintage science fiction paperback from the mid-1960s, its pages crumbling into a fine powder of allergens, typically does to me what the Madeleine dipped in tea did to Marcel Proust or what the “blue note” does to the jazzman. It “sends me.” My romance with science fiction is likewise altogether intertwined with the intellectual struggles (many of them self-struggles) in which – again in childhood and adolescence – I have found myself involved and (as it were) “under arms.” What is a value? Is the mundane world all that there is or do human beings justly aspire beyond it? We phrase these questions latterly but we experience them before we can phrase them. We experience them in inarticulate frustrations and in inchoate certainties. Because I grew up entirely without religion, science fiction became for me, no doubt, a substitute faith, but by no means an unworthy one. Like any adherent of a faith, I defended mine; I defended its incoherency, its wildness, its Gnostic exoticism and exclusivity. I defended it to supercilious female English teachers in junior high school and in high school; I defended it to scoffing relatives who, incidentally, would have regarded any reading as both suspicious and unhealthy.

If it were so, the germ had taken hold and would not let go. Afflicted an examiner would have found me and afflicted I remain. The astute examiner would have pointed out that my espousal of science fiction, undoubtedly indicative of a neurosis, had also rendered me parochial in my taste, resistant to the earthbound genres, and more than a bit nerdish in my preoccupation. On the other hand, I was certainly no more restricted in my mental orientation than my motorcycle- or surfboard-riding peers (supposing peers to be the right word) at Malibu Park Junior High School or Santa Monica High School , or than the Brady Bunch- and boy-obsessed girls of the seventh and eighth grades in the former locale. When I review my Spartan yearbooks from 1966, 67, and 68, I see a raft of hormonally distorted faces, each one in its own way registering the serial humiliation of being thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen years old. Only a few blessed exceptions look anything like happy. At least, in imaginative stories, I could rise above the dreary plane of the post-infantile erotic agony with its invidious indignity of what, in junior high school, goes under the name of “popularity.”

As for the meaning of science fiction, redemption from the insipidity of quotidian existence strikes me as a good place to begin. It provides the theme in Colin Wilson’s serious autobiographical discussions of science fiction in the frank Voyage to a Beginning (1966) or in the feisty “Autobiographical Introduction” to his study of Religion and the Rebel (1957). Among the figures that Wilson takes for analysis in Religion and the Rebel are Jacob Boehme, Søren Kierkegaard, Oswald Spengler, Rainer Maria Rilke, Arnold Toynbee, and D. H. Lawrence. No one could justly accuse the Voyage-author of frivolity, vulgarity, or parochialism. Born in Leicester in 1931 of working-class parents, Wilson grew up in quasi-poverty exacerbated by the prejudices of the British class-system; he would later establish himself as a writer and produce a half a dozen science fiction novels of a high literary order as well as sixty or seventy other books of both fiction and nonfiction. His Outsider (1956), the first English-language study of Existentialism, became an unlikely nonfiction bestseller, putting him on the cover of Life magazine. He had been reacting against his environment since before his teens. “My father,” Wilson records, “never read a book, and he liked spending his evenings in the pub… So money was short, and my mother often cried.” Wilson soon discovered intellectual proclivities at strong variance with the domestic, with the neighborhood, tone. Having caught on early to reading, he read. At first he read haphazardly, by grace of gifts, but he also availed himself of the school library. He remembers, at age seven, seeing “an illustration of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea showing Captain Nemo discovering Atlantis.” Old editions came with judicious illustration that complemented rather than competed with the text. Wilson continues: “I asked questions about Atlantis, and was… amazed that no one had bothered to tell me about such a fascinating subject.”

The same amazement would attach to the theory of Mars as an abode of life when Wilson encountered it, as he tells, three years later in the book of Marvels given to him by his uncle. Wilson’s grandfather introduced him to science fiction, giving him a back-issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories; this also happened during the war, when American periodicals were otherwise unobtainable in Britain. Judging by Wilson’s description of one of the stories, about a bit of laboratory-produced protoplasm that grows in size and ends up swallowing an ocean liner, it would have been the April issue of 1931, which features the tale on its cover. “I read with a sense of revelation,” Wilson writes: “I became a science fiction addict; I thirsted after the magazines like a dipsomaniac after whiskey.” While the war-economy kept current numbers of the American pulps off British newsstands, “many bookshops ran an exchange system – you could not buy one of their science fiction magazines, but once you had one you could exchange it any number of times on the payment of a few pence.” Craving a collection of his own, Wilson schemed quite without conscience to get one: “I turned my skill as a thief to full account. On one or two occasions I was almost seen by the shopkeeper, as I was about to slip a magazine under my jacket; but the collection grew until I had about sixty magazines. Amazing Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories, Fantasy Magazine, and so on. I cannot remember how long the passion lasted, but it was certainly several years.”

This “passion” for science fiction worked in parallel with a like passion for science; both passions stemmed from a growing sense of deficiency in the social environment. People began to impress the young Wilson as vague, dull, and foolishly content with their small portion. “Man might be, on the whole, a contemptible creature, but this was because most men were too lazy to care about anything beyond their immediate needs.” In describing the Leicester of the 1940s and early 1950s, Wilson recalls “hairsplitting spite and malice… an overwhelming monstrous triviality, a parasitic triviality that ate its way into all values.” Stories of magnificent research and the facts of physics or chemistry hinted at a keener world: “I had never met anyone who was in the least interested in ideas, or in knowledge for its own sake… but it was possible to transcend human limitations by an idealistic devotion to knowledge.”

For myself I make no complaints of poverty or class-prejudice; nor was the social environment of my childhood and youth so mean as Wilson makes his out to have been. A sociologist might well have exhibited the Bertonneau household as an exemplum of the post-war middle-class economy and of the ideals of comfort and independence that it entailed. My native ground, Highland Park, formed a dormitory annex of Los Angeles, on whose City Fire Department my father served as an officer – a captain when I was a child and a battalion chief as I entered adolescence – of some considerable distinction. He brought to bear on the famous Bel Air Fire in 1962 a new tactic that at last contained the hitherto uncontainable flames; he later gained a reputation as the expert in the suppression of chaparral fires, the fiercest sort of wildfire, in the Hollywood Hills and the Santa Monica Mountains. Our house, which my father had built himself, stood at the top of Division Street midway between York Boulevard to the north and North San Fernando Boulevard, with its Southern Pacific Railroad freight marshalling yards, to the south. The yards represented old, heavy industry of the Los Angeles Basin; they had increased in size and capacity during the war. York Boulevard represented the new commerce of shops and small businesses; most of it consisted of cheap cinder-block construction of the type later to take the name of strip-mall. My parents would contribute to it as entrepreneurs of the “York Boulevard Wash-o-Matic,” a coin-laundry in a whitewashed building with large plate-glass windows looking out on the passing traffic.

Highland Park lies adjacent to Pasadena in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains under the shadow of Mount Washington, the most prominent of the anticipatory summits. The houses on Palmero Drive, behind us and above us, all corresponded to the hillside type, held up by tall piers. Among the civic amenities of the neighborhood there were several ambitious public stairways. One was always slogging uphill or downhill on steep sidewalks, when not on one of the stairway easements. I attended Toland Way Elementary, walking the short distance with my buddies – Tommy Santoyanni and Mike Mitchell – starting in the third grade. Instruction seems to have been competent. The Dick and Jane books played a role in the second-grade curriculum; in the third and fourth grades we used other “readers,” so unmemorable in their content that I cannot record so much as a single fact about them. Nevertheless I knew what books were. My father read books, although he never, to my knowledge, read fiction. He liked engineering and the practical sciences; he regularly brought home copies of Scientific American from the fire station, taking some pride in understanding the mathematics of what, in those day, were serious technical expositions. For the last twenty-five years, at least, Scientific American has been entirely popular in its orientation, avoiding quantitative formulas. My mother was my father’s second marriage; I had (and still have) a surviving half-brother from the first marriage, sixteen years my elder, who, in the early 1960s, had finished a bachelor’s degree in Engineering at California State University at Northridge and had found employment at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation in Burbank in redesigning the ejection-seat of the F-104 Starfighter. My father’s concurrent interest in mechanics and engineering sprang, I imagine, from his competitiveness with my brother, who had by then outstripped the paterfamilias in education. My mother kept up with The Los Angeles Times and The Herald Examiner, as did my father. She read The Reader’s Digest, but she did not read many books.

For family entertainment, the house featured a built-in black-and-white television in the living room, which we watched a good deal. The speech of President Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis stands out in memory. So does the calm voice of Bob Keeshan as “Captain Kangaroo”; so does much other early-morning children’s fare. Later “Chiller Theater,” a Saturday-afternoon program of “Frankenstein” and “Mummy” movies from the 1940s and 50s, exerted its interest.

Apart from Cold War worries, life unfolded smoothly on the flat surface of existence – flat despite our topologically wrinkled environment in the Highland Park hills and arroyos. Even the Missile Crisis, with its raid on canned food in the supermarkets, only interrupted the regularity of things a little. I remember the collision of carts in the grocery aisles and a lady-neighbor uttering a bad word against my bewildered mother. A bland normality otherwise prevailed. I associate my elementary education at Toland Way, as such, mainly with endless ball games on the schoolyard, with the tedium of arithmetic worksheets, and with a few titles from the school library.

The books bore the authorial signature of Ruthven Campbell Todd. That science-fiction-like innovation, the Internet, gives Todd’s dates as 1914 – 1978 and credits him, among other things, with a study of William Blake’s engravings. Todd wrote a four-item series of children’s books in the 1950s under the generic title of Space Cat, illustrated by Paul Galdone. The eponymous two-word initial title appeared in 1952, followed by Space Cat Visits Venus (1955), Space Cat Meets Mars (1957), and Space Cat and the Kittens (1958). “Flyball,” the feline astronaut, belongs to “Captain Fred Stone,” who often fares solo between planets. Stone pioneers and explores. Todd shows us space travel from the animal’s perspective, mystified at all the fuss, disconcerted at first by zero-gravity, but fond of his master. The conceit appealed to the second-grade mind, especially to the one undernourished by Dick and Jane. Is it a backwards projection from the adult perspective or is it a thought actually entertained by an eight-year-old at the time? It irritated me that Dick and Jane supposedly represented me; that the authors (it must have been a committee) expected me to respond because Dick and Jane romped, as eight-year-olds, through the second-grade school scene and about the lawns of their neighborhood just as I did. One need not know the word jejune to come away from an insipid meal dissatisfied and still hungry for a meatier repast. Some part of me craved – what to call it? – Otherness in the story telling or a deeper infusion of fancy or imagination. Aesop, the fabulist, understood this principle. He cast his moralities as animal-stories, thereby overcoming the audience’s resentment against a too-obvious holding up of the mirror to itself; the animal-story speaks particularly to children who come to terms with the underlying lesson through the totemic images. In Space Cat Todd had concocted an Aesopian formula for the Sputnik-era. He also drew on that lore of planetary speculation deeply rooted in the popular astronomy of the Nineteenth Century.

A Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius (1859 – 1927), had speculated about Venus in his Världarna i Utveckling (1906), translated as Worlds in the Making (1908): the planet’s cloudy exterior, the Swede guessed, must make for a hot, swampy, surface via what we Twenty-First Century types would denominate as “the Greenhouse Effect.” The Venus of Arrhenius knew torrential rains in perpetually hot weather and probably supported a fauna of mega-reptiles long since extinct on earth. Todd’s story escapes me entirely but the setting remains vivid even though it certainly qualified as absurdly out of date at the time. By the 1950s astronomers knew Venus to be a ferociously hot, dry planet with a poisonous, corrosive atmosphere. Every time NASA sends a probe there the picture worsens. Todd’s Mars, where Flyball meets a lady-cat, assumes the late-Nineteenth Century model of a desiccated world, red with planetary rust, crisscrossed by ancient canals, with a thin high-mountain atmosphere. This too represented a superseded notion, but no eight-year-old either grasped the factual obsolescence or cared about it. A bit of sentient lichen, gathered up from the red soil and placed in a locket, enables Stone and Flyball to communicate directly for the first time. The lichen is a Martian. He minds not at all yielding part of himself to mediate the dialogue of feline and human; he is a quietist and an altruist, as the wise of elderly worlds are supposed to be.

Space Cat and the Kittens follows logically from Flyball’s amorous luck on the Red Planet; it concerns a world of Alpha Centauri where the whole mixed crew comes face to face with (nothing less than!) miniature dinosaurs. Todd’s books suggested a realm of imagination that could take one in wonder and merriment into new non-empirical worlds; they contrasted radically with the sidewalk milieu of Dick and Jane. Imagination belongs among philosophical concepts of a sophisticated type and Space Cat belongs among forgotten trivia of children’s literature; what triggers imagination need not be exalted. The resultant transformation of awareness justifies its cause and puts one in debt to it. My debt is to Flyball, not to Dick and Jane.

About a year after the time when Todd’s books first delighted me, my parents gave me a small telescope for my birthday; it came with a manual, Sky and Telescope, that explained the principles of reflection and refraction, offered a tour of the constellations, and retailed a few largely discredited claims about the planets – culled, it seemed, from science-journalism of the 1920s and 30s. A section devoted to Mars showed a fuzzy color photograph from the two-hundred inch Hale Telescope at Mount Palomar; the prose referred to an old assertion, probably that of Vesto Slipher (1875 – 1969), that spectroscopic analysis of sunlight reflected back from the Martian surface indicated organic compounds in the soil and that this “confirmed” the hypothesis of vegetation as the cause of seasonal color-changes noticeable on the Martian orb. I tried to find Mars in the night sky but never succeeded. I advocated the life-on-Mars hypothesis anyway, as though expertise made me an authority. My brother, a strictly hard-science type, refuted me, which only made me more adamant about the “Fraunhoffer Lines of organic molecules” in the decades-old spectrographic readings, Joseph Fraunhoffer (1787 – 1825) being one of the establishers of spectroscopy. Dan must have mentioned two names that would acquire significance for me, those of Percival Lowell (1855 – 1916) and H. G. Wells (1866 – 1946), the former as the likely source of the life-on-Mars hypothesis and the latter as author of a story called The War of the Worlds, first published serially in The London Daily Telegraph, and nearly simultaneously in the United States in The Cosmopolitan Magazine, in 1897. Wells’ novel had been adapted infamously as a radio drama in 1938 and as a film in the early 1950s, 1953 to be exact, when Dan earned his living managing a movie theater in the San Fernando Valley.

My parents read almost no fiction, as I have noted, but readers they were nevertheless of journalism; they did therefore, on the evidence of it, place a value on literacy, although they would not have used that word. My father took me regularly to the Colorado Street branch of the Los Angeles Public Library from the time I went to Kindergarten in 1959. I wanted to read The War of the Worlds, although, having never read a novel before, I knew not what tackling or assimilating one entailed or even what the term novel meant. I enquired of the children’s librarian, a lady who had led me to many satisfying books, after Wells’ story. She said to my father and to me that The War of the Worlds formed part of the main library rather than part of the separate children’s collection, to which my card gave me access, and that my father would have to check it out for me. It did not have a volume of its own but was part of an old edition from the 1940s called Seven Science Fiction Novels of H. G. Wells, printed (it so happened) in double columns on noticeably thin paper.

Both the librarian and my father expressed some skepticism about whether I had sufficient skill to con such a tome, but the library having released the book into our charge, the Novels accompanied us home. I hefted it, a bulky affair, in the car. The cloth binding had a peculiar feel to it which remains an element of the total experience, a texture of stiffened fabric under the fingertips. In fact, I had never previously handled an adult book, but only the junior fare with laminated cardboard covers, whose feel was entirely different. The Seven Novels seemed bereft of all illustration, as I flipped through the pages, except that sections (I doubt that I possessed the word chapter) boasted first sentences whose initial letters consisted of large florid devices. There was weightiness to it. The item held for me something of the character of a newly discovered Grimoire for its long-seeking devotee: a promise of secrets to be revealed, of a world about to be flung open, and of an expansion of the mental tone.

II

Of all the hundreds or even thousands of authors who might have selected themselves to be my instructor in genuine literacy, it is a piece of luck that the spirit of Wells winged down to me at that moment out of the literary Parnassus. Wells himself had received the grace of the written word – and of literature – at age ten or so, when, as he tells in his Experiment in Autobiography (1934), he got free run of a deceased gentleman’s library in the house where he mother kept the scullery.

Terms like grace and salvation hardly seem out of place, although Wells (1866 – 1946) often wrote meanly of religion and of its vocabulary; his irate Crux Ansata (1944), a wartime attack on the Catholic Church, was penned, apparently, using superheated bile in the reservoir. What to say? Biliousness marks, quite as it flaws, the prophet, whether of the Hebrew-Christian or the Enlightenment-Materialist variety. Not that Wells corresponds exactly with the garden variety of materialist (hardly): but a spirit of vatic conviction, of righteous dissatisfaction with all complacency, charges the opening paragraph of The War of the Worlds, making it rhetorically dazzling and homiletically unforgettable. After hearing its cadences once, for example, my ten-year-old recited two or three of the key sentences back to me with impressive accuracy. Wells’ language must have enthralled me deeply when I first grappled with it, too, whether I understood it or not, for it has resurfaced regularly in my memory ever since, just as it does now. To the objection that the subject has confused later interest with original appreciation, the response is that without original appreciation, as inchoate as that was, no later interest could have asserted itself. The presence of the latter therefore guarantees the presence of the former.

Inassimilable as this grand philosophical apostrophe is to cinema, all three film-adaptations of the novel (Wells referred to it as a “scientific romance”) try to appropriate it so as to frame the action. Yet the three film-directors – Byron Haskin, Timothy Hines, and Stephen Spielberg – cut fearfully the sequence’s most poignant sentences, as if these would alienate their audience. Maybe it is so. The great Wellsian paragraph humbles mankind and might indeed provoke annoyance among mere entertainment seekers, if only they deigned actually to attend its grand indictment of their insouciance.

The secondary literature on Wells often quotes The War’s loftily eloquent prolegomenon – that great and objective looking-back at a catastrophe only barely survived. I apologize for quoting it again in toto, but I must:

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same. No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space, or thought of them only to dismiss the idea of life upon them as impossible or improbable. It is curious to recall some of the mental habits of those departed days. At most, terrestrial men fancied that there might be other men upon Mars, perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to welcome a missionary enterprise. Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds what ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. And early in the twentieth century came the great disillusionment.

The paragraph traces an unexpected itinerary, from disbelief of a kind – not, we note, belief – to “disillusionment.” This disbelief, entirely passive, Wells, comme romancier, links to a calculatedly hyperbolic “infinite complacency,” posited as characteristic of his fellow men in the obsessive mercantile “concerns” (so he puts it) of their Edwardian ascendancy. Wells the scientific socialist and Wells the revolutionary technocrat inhabit the sentence, whose reformist and redistributionist tendencies would achieve fantastic articulation in later phases of their author’s production. The ominous quality of the paragraph’s opening sentence deserves notice, too: those “intelligences greater than man’s” who monitor earthly activity from afar demote and so also castigate terrestrial intelligence by their mere existence; their mortality, which they share with us, disarms their clinical interest in our globe not at all. We lull ourselves in a serene assurance while the Martians scrutinize us, “as a man with a microscope might the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water,” thus demoting us even further, by analogy, down the ladder of zoological and cognitive sophistication. A bit later on the Martians become, by another analogy, “minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic.” The biologist’s eye at the aperture of the microscope geminates in the multiplicity of “envious eyes” that examines us by telescope from its planetary redoubt. At first the infusoria occupy the specimen-slide, but quickly the simile transforms the whole earth into the specimen-slide and we occupy it, quite as obliviously as our unicellular counterparts do theirs. The notion of “a missionary enterprise” rings quaint, for it belongs to our vulnerable parochialism.

But what, at the time, might these odd periods have signified to their most callow and bewildered of readers? Wells’ orotund phraseology posed numerous difficulties; not least of these, to slant the observation from a mature reader’s perspective, was the satisfyingly rich and provocatively exotic vocabulary. The paragraph also subordinates its clauses, deals in parallel constructions or analogies, and exhibits peculiar material qualities when read aloud. I will come to the last. Let us begin with vocabulary. To scrutinize, transient, complacent, infusoria, terrestrial, beasts that perish, intellects, disillusionment; these words, delectable to a canny reader, rarely belong within the lexical purview of fourth-grader, from which typical ignorance the lad in question could have claimed no exception for himself, of any kind, in that tail-finned and boldly orbital year, 1963. Nor did he look the words up, as he had not yet acquired that gentle habit. Now other locutions I did more or less recognize, while struggling with their couplings, or with their contexts.

The term empire, for example, I conned, and so too matter; but the novel construction “empire over matter” baffled me, as it does my undergraduates today. To the rescue of the reader in other cases came a rudimentary scientific education gleaned partly from school lessons and partly from voluntary non-fiction reading in books and magazines. Life and U.S. News and World Report came into the Bertonneau household; the Sunday supplements of The Los Angeles Times included much science and technology reporting. (It was the Space Age, after all.) My mother and father had given me as Christmas and birthday gifts various Encyclopedias, of this and that, in laminated covers; they stood on a shelf in my bedroom with the astronomy book cum telescope-guide. My son owns similar useful books, and appeals to them often.

From their juxtaposition with familiar terms, some of the unfamiliar ones made sense preliminarily, as, for example, infusoria. These belonged, I could grasp, with the “transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water,” which the hypothetical “man with a microscope,” as Wells says, “might scrutinize.” The adjective transient aside, the concreteness of the image helped a good deal, for I knew what a microscope was, having peered through one in class during a science demonstration. So infusoria were “germs,” as fourth-graders called them, a gloss that suggested the plural. I knew a word, paramecium, which denoted a tiny creature on the order of a “germ,” having encountered it in a comic book with an illustration.[1] The teacher, in introducing us to the microscope, had said that we would see paramecia on the slide. Scattered references thus congealed in a new word, while the new word took its place in a sentence whose elegance must have reached me although the word elegance lay beyond my ken. The odd sounding to scrutinize clearly meant what one did when one stared through the eyepiece either of a microscope or a telescope. What about terrestrial? The sentence refers to what “terrestrial men” imagined concerning living beings on Mars, so that one could easily enough understand that the term had something to do with the earth. “Gulf of space,” while slightly peculiar, resembled, for example, “Gulf of California,” which appeared on the maps that we studied in our geography lesson. As a geographical gulf is a hiatus of water between to arms of land, a “gulf of space” must be the hiatus of vacuum between two worlds in a planetary system.

Here, however, the tyro reached a limit of comprehension, for the ensuing phrase – the one dedicated to those “minds that are to our minds what ours are to those of the beasts that perish” – refused to resolve into an image; it merely and yet magically resounded, so many vibrations on air. I guessed that the “intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic” who “regarded this earth with envious eyes” were the Martians, but the queerness of what went before unsettled any certainty.

A previous remark contends that The War’s opening paragraph “exhibits peculiar material qualities when read aloud,” an epiphenomenon of the written text that one usually associates with lyric poetry and that implicates one of the weirdest facts about the understanding of the written word. While I could not have glossed the Wellsian analogy of “minds that are to our minds what ours are to those of the beasts that perish,” I could nevertheless relish its syllables, and I did. A fastidious Englishman will sharply differentiate are and our; Americans, being lazy about elocution, tend to blur the distinction. Ask undergraduates to read the sentence aloud and they always stumble over the close iteration of are, our, ours, and are, because they want to assimilate what ought to be two different vowel-sounds under an assonance, one that rhymes with ba,, as in a bar of soap. Properly the possessive our, ought to rhyme with power or hour, a noticeable diphthong if it were not quite two syllables, while are continues to sound like bar. Every time I tried to read the recalcitrant sentence audibly, I met up with the exact precursor of the undergraduate pronunciation-scandal. It bugged me. On the other hand, reading it repeatedly in an increasingly petulant and exasperated mood charged the unyielding words with the character of an incantation. In The Nature of Things, Book I, Lucretius characterizes Heraclitus as “illustrious for the darkness of his speech, though rather among the lighter-witted of the Greeks than among those who are earnest seekers after truth.” A ten-year-old necessarily belongs among “the lighter-witted,” but my stupid fascination with unpronounceable syllables implied no associative defect in its object, as Lucretius implies of Heraclitus; on the contrary, the Wellsian figure generates the very chiaroscuro in which the events of his tale will fall out. Knowledge and ignorance, cosmopolitanism and parochialism clash on every page of the romance.

The adamantine opacity of the simile for the novice reader (objectively, it is anything but opaque) becomes in retrospect a key paradox of the acquisition of literate understanding. No doubt Plato had already formulated the paradox in the Fourth Century BC, but contemporary people, assuming they ever knew it, have forgotten the formula. It is this: knowledge quickens in one of the forms of its opposite, namely ignorance; the form of ignorance in question is a transfigured ignorance that both knows itself for what it is and recognizes merit in its object even as it fails fully to comprehend that object. The prisoner in the cave blinks painfully when the periagogê occurs and he first sees the raw firelight rather than the flickering shadows it casts; he knows that he is seeing something, but he as yet has no concept for capturing it. The raw firelight shatters the percipient’s former complacency, but it also inspires him with a belief, not yet expressible, that the new, disorienting experience has subsumed all else in its importance. As I forced my way paragraph by paragraph and page by page through Wells’ romance, I grew dizzily familiar, not with a continuous story, but with flashes of discernible incident in a welter of wordage that refused to come into focus. The narrator’s summary of probable conditions on Mars, which comes in Book I, Chapter the First, of The War,, just after the introduction, presented no difficulty: “Even in its equatorial region the mid-day temperature barely approaches that of our coldest winter” and “its air is much more attenuated than ours.” So much the outdated science of my astronomy book had already told me. The opening of the first Martian cylinder in Chapter the Fourth and the narrator’s observation of the alien creature likewise occur under vivid imagery, in the manner of a journalistic report. There are “the peculiar V-shaped mouth with its pointed upper lip… the Gorgon groups of tentacles… the evident heaviness and painfulness of movement due to the greater gravitational strength of the earth” and “above all, the extraordinary intensity of the immense eyes.” Those eyes first peep over the narrative horizon in the opening paragraph, where Wells establishes that they have indeed been watching the earth for a long time, methodically preparing their invasion.

The revelation of the tripod fighting machines in Chapter the Tenth (“In the Storm”) also stands out starkly in my memory. These form one of the salient conceits of the romance, suggesting the technical sophistication of Martian industry and giving the Martians a tactical mobility unavailable to the horse-drawn ordnance of His Majesty’s field artillery. Haskin, in his 1953 film, dispenses with them, substituting manta-ray-like magnetically levitated vehicles. Hines and Spielberg succumb to their charm and attempt to realize the Wellsian image; Hines does it with less technical sophistication than Spielberg but with a greater faith to the text. As for The War itself: The narrator having driven his wife to Leatherhead, to get her out of harm’s way, he is returning by night with a hired “dogcart” to Woking, where he has promised to return the conveyance to its owner. In pouring rain, with lightning stabbing through the darkness and thunder smashing against the air, the unnamed first-person story teller has “an elusive vision,” in which he makes out “a swift rolling movement” behind the trees on Mayberry Hill: “A flash, and it came vividly, heeling over one way with two feet in the air, to vanish and reappear almost instantly as it seemed.” Wells poses rhetorically, “Can you imagine a milking-stool tilted and bowled violently along the ground?” The horse bolts and the dogcart heels over, throwing its driver into the mud; dazed, he tries to gather his senses amidst “blinding high lights and dense black shadows.” Trying bewilderedly to assemble half-understood bits and pieces of text was precisely what I was doing, for who can read a novel who, not knowing the word novel, reads one for the first time? The narrator’s interpolations of his younger brother’s experiences into his account of the Martian invasion entirely defeated me.

As I could, in my mind’s eye, visualize the tripod war-machine (that “walking engine of glittering metal”), however, so I also could visualize the valiant sally of the ironclad steamship Thunder Child against the alien mechanisms. In Book I, Chapter the Seventeenth, Thunder Child manages to destroy two Martian machines that have waded into the English Channel before the heat-rays of their companions combine to sink her. The Colorado Street Library had afforded me an illustrated book called Ironclads of the Civil War, so that I knew what an armored ocean-going “ram” looked like. It looked like the C.S.S. Virginia, on a larger scale. Otherwise, The War baffled and amazed me. It put me in some doubt – because of its first-person mode and its exact topography and onomastics – whether in a fashion I could not fathom it might be true. I sensed nevertheless what Colin Wilson, in Science Fiction as Existentialism, reports that he senses when he reads Wells’ fin-de-siècle scientific romances: “Wells might have enjoyed showing the human race decimated by Martians, or reduced to the level of thoughtless children by technology, but the basic impulse behind the stories [is] a kind of healthy delight, the kind of thing you feel by the seashore on a windy day.” I made an effort to read The First Men in the Moon (1901), included in the same volume, but found no purchase in the chatty opening chapters, which concern not the moon but rather the narrator’s dubious business dealings, his failure, and his ducking his creditors in the countryside. The First Men in the Moon is a fine story, but it does not pull a reader in as The War does. I would, of course, reread The War many, many times although, in the aftermath, I seem to have satisfied myself with other, less ambitious fare – a series of books by Willard Price (1887 – 1983) concerning two brothers, Hal and Roger Hunt, who have various adventures in exotic settings. Amazon Adventure, South Sea Adventure, Volcano Adventure, African Adventure, and Underwater Adventure, written between 1949 and the mid-1950s, enjoyed terrific currency among the fourth- and fifth-grade boys of Toland Way School. My classmate Charles “Chuck” Hiscock began the craze for them; his parents were medical doctors, much respected in a neighborhood where few people held college degrees. Their professional standing and associated prestige settled an aura of healthiness on the Adventure books. The teachers approved of Price and properly encouraged us to make him a hobby. The Hunt brothers exerted their attraction, to be sure, but they never fought off a Martian attack.

When I spoke of The War no one deigned to take an interest in it. My fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Elna Baker, went so far as to say something vaguely disparaging. But when I attended the sixth grade at the Mayall Street School in Granada Hills, where we lived for a year (1965) on our way to Point Dume in Malibu, my teacher Mr. Logue saw me one day with a paperback of Wells’ story, and he praised me for my selection. He even remarked to me about the immediacy of the first-person mode. “It’s as though Wells himself had experienced all the events,” he said; “he makes himself the hero of the story.”

III

In Ethics and Infinity (1981), interviewer Philip Nemo asks philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas about the relation of reading, of books, to life and to thought. “How does one begin to think?” Lévinas answers: “It begins with the traumas and buffetings to which one cannot give any verbal form – a separation, a scene of violence, a sudden awareness of the boredom of time.” It is in the reading of books, Lévinas continues, that the “initial shocks acquire the form of problems, given to thought.” Just this pattern appears in Colin Wilson’s intellectual autobiography, Voyage to a Beginning. Books gave Wilson, in his early adolescence, a vocabulary for assessing his dissatisfactions, and shapes and images to lend a structure to the unprocessed stream of life and events – particular books. For at age eleven or twelve, as Wilson says, the author of The War of the Worlds “was the writer I admired most.” Wilson adds, “I suspect that I was aware only of Wells the story teller and was indifferent to Wells the prophet.” Wells opened the vista of science which seemed to Wilson the anodyne to lower-working-class tedium, of his immersion in which he had become acutely conscious. Lévinas, a Lithuanian Jew born in Kaunas in 1903, had to adjust to a more radical type of alienation and absorb harder blows than those that afflicted Wilson, but the literate awakening remains the same in its basic structure. Wells never pretended to be a philosopher, but he knew himself as a thinker whose thoughts might be helpful to ordinary people in the throes of their disappointments. As science fiction writer Jack Williamson (born 1908) puts it in H. G. Wells, Critic of Progress (1973): “He is never a systematic thinker…. Yet the casual insights that illuminate his early fiction seem truer to me now than most systems of philosophy.”

A glimpse of Mars as an inhabited world, in which others disdained to take a share, along with two household moves in as many years and a peculiar isolation just on the verge of adolescence, provoked me into my dull version of thinking. My plight pales, of course, before all real tribulation, so much so that my calling attention to it will likely strike others as petulance. North American middle-class schoolboy-troubles withstand no comparison with those, say, of Wells, condemned to life as a draper’s apprentice, or Wilson, or (God knows) the redoubtable Monsieur Lévinas, in their respective trials. The adjective banal describes my afflictions perfectly, but (this is perhaps my point) the context of those afflictions also qualified as banal and thus constituted a problem for me, however low-grade; mine was a representative crisis, I would suggest, of postwar ennui and disgruntlement. Technical developments, too, played a role in my reaction to a jejune environment. I discovered myself in a contretemps with certain empirical observations, of a physical-astronomical character, which did not, in fact, admit of dissent. Unlike Wilson, then, I sought no solace in science, but rather I sought it in a stubborn pitting of a contrarian’s hope against science, justification for which perverse position I took from the genre called science fiction. The empirical observations concern the planet Mars, but before I specify them, I must say that, in July 1965, my parents sold their Highland Park house on Division Street and moved us into temporary quarters in the San Fernando Valley. Exactly a year later, they moved us again into the new house that they had built on a sloping hillside lot on Point Dume, overlooking the Santa Monica Bay, in Malibu. Granada Hills lies not far, in straight miles, from Highland Park; Point Dume is again not so far, in straight miles, from Granada Hills. At eleven and then again at twelve, however, the fact of two removals in as many years counts for something like the divestiture of one’s world.

Despite the beauty of the nighttime view across the Bay – all the lights of the coastal cities from Santa Monica to Redondo Beach ablaze, with passenger jets hovering and glowing over L.A.’s airport – and despite the sylvan character of the as-yet-undeveloped Point-Dume headlands, the new neighborhood, because of its isolation, could induce a dreary mood and inspire a conviction of exile. Taken away from his social situation, the twelve-year-old arriviste must assume a considerable burden of loneliness due to non-initiation in the local scene; he will yield to the provocation to think, not systematically, but, broodingly by skips and leaps, over the desolate topography of his life. Insofar as he is already a reader, the cultural barrenness of summer vacation spent willy-nilly in a strange land drives him with redoubled intensity into his books. That these books now included The Flying Saucer Conspiracy (1955) by Donald E. Keyhoe (1897 – 1988), Flying Saucers: Serious Business (1965) by Frank Edwards (died 1967), and the colorfully illustrated titles about space flight by Willy Ley (1906 – 1969) and Chesley Bonestell (1888 – 1986) made his refuge more desperate, but also richer in texture, than it might otherwise have been. Keyhoe’s Conspiracy devoted at least one chapter to Mars as a possible origin of the UFOs; it invoked the disqualified Lowellian theory of the planet and discussed anomalies on that world recorded by astronomers since 1900. Comic books had by this time impinged on me, too, with their bug-eyed monsters from a plethora of populated worlds, most of which, in the climax, the hero destroyed with a convenient super-weapon. My father and mother had schemed a different objective – the wholly admirable one of getting their kids away from an increasingly toxic urban environment into cleaner air – but it would not develop that way, exactly. I rode the local streets on my bicycle, hoping to meet new acquaintances, but only a few scattered houses dotted the area, many recessed from the road on one- or two-acre parcels and further screened by fences or sentinel-lines of eucalypti. Eric Olson and his brother Lee, who lived on Grayfox Street, pretended to concentrate on their fraternal basketball game and cold-shouldered me. The Byron Haskin movie of Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) seemed correlative to the situation. My father had taken me to see it shortly before we left Highland Park. My mother told me that I would make friends when I began the seventh grade at Malibu Park Junior High School in the fall, a prediction that I stubbornly doubted and a prospect-in-the-offing that I heartily dreaded.

The offense of science against everything noble in the Super-Lunar Realm all the way up to the Empyrean stemmed from a NASA-project called Mariner, consisting of a series of unmanned probes sent off by rocket to Venus and Mars in the early 1960s. Mariner 2 had flown past Venus on 14 December 1962, annihilating the Arrhenius theory of a wet planet resembling the earth of the pre-dinosaur era: earth’s “sister planet,” enveloped in thick, smog-like clouds, boasted a surface temperature hot enough to melt most metals; she offered ferociously little in the way of hospitality to life. It fell out indeed that the second planet from the sun also kept one side perpetually exposed to the solar primary, so that thousand-mile-an-hour winds circulated over the glowing rocks, bearing with them a finely particulate suspension of hydrochloric acid. One might perish in six or seven unpleasant ways on the hard-hearted, hot-blooded Evening Star, once worshipped by Syrians and Greeks and Romans as a goddess of peace and love. The Space Administration had launched Mariner 4 atop an Atlas rocket on 28 November 1964, around the time that Seven Science Fiction Novels of H. G. Wells came home to Division Street from the Colorado Street branch of the L.A. Public Library; its cameras clicking, the robotic explorer swooped past Mars on 14 July 1965, just about when we shifted our belongings from Division Street to Devonshire Boulevard for the twelvemonth hiatus between permanent domiciliary arrangements. Mariner 4’s rendezvous with its target would prove epochal for planetary science; it would inspire among astronomers not just skepticism about the possibility of life, present or past, on other globes than the earthly one, but rather dogmatic hostility.

The incumbency would devolve on me – and on a few die-hards like me – to oppose that dogmatism, as a matter of faith and all on our own if no allies joined us. Or so I thought to myself in the light of my indignation. At least, in thinking these things, I would come to know who I was.

For each black-and-white frame transmitted back to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena set a nail in the coffin of extra-terrestrial romance. The hopefully named Martian places that now came into killing focus – Elysium, Amazonis Planitia, Mnemonia Fossae, and Orcus Pratera, most of them christened by Lowell in his maps – revealed a world hellishly frigid and dust-dry, shattered by a million years of meteoric barrage, where the only air, a whiff of carbon dioxide, was indistinguishable from a total vacuum. Newspaper headlines shouted the intelligence of a dead world, as though the information was a triumph. In his Technicolor dioramas accompanying Ley’s text, Bonestell had remained willing, in the mid-1950s, to show blue watercourses, arguably artificial, bisecting the red Martian deserts, and greenish lichen-like discoloration splotching the red Martian rocks. The conspiracy of engineers, with their thick-rimmed glasses and thin black ties, had roused us meanly from the fascinating dream vision; they had turned the heat-ray of their hard, digitalized facts on the fabulous gestalt of our poetic faith. Two authors offered the alternative to this new bland reality of antiseptic worlds, the alternative in which a vital solar system refuses to lapse into a meaningless datum, and in which everything is not mere dead matter, either frozen or molten.

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875 – 1950) wrote in the heyday of Lowellian speculation about the Red Planet; Ray Bradbury (born 1928), a Wisconsinite by birth but an Angeleno by choice, constituted a mostly postwar phenomenon, but his spirit dwelt with those of Burroughs and Lowell. I went indeed to Malibu Park Junior High School in the fall, meeting up with George Katz and the three Cunningham brothers – Tom, Jim, and Alan, in descending order by age – who, among them, had read Todd, Wells, Price, and items of the UFO-literature and who attracted me to them by cultural gravitation. Friends are the people with whom we can converse about mutually stimulating topics and through whom we see our way into congenial novelty; they are the people with whom we are commonly at odds with others and who share our peculiarities. George would put me on to Burroughs and Tom would point out Bradbury in the particular manifestation of his Martian Chronicles (1950).

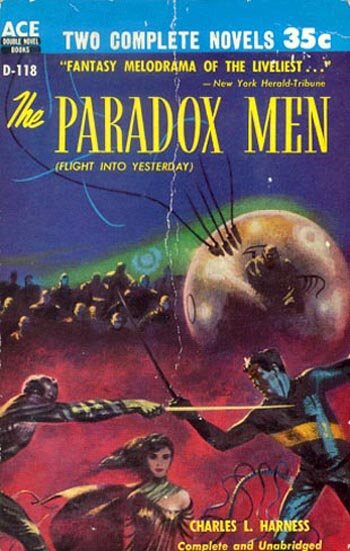

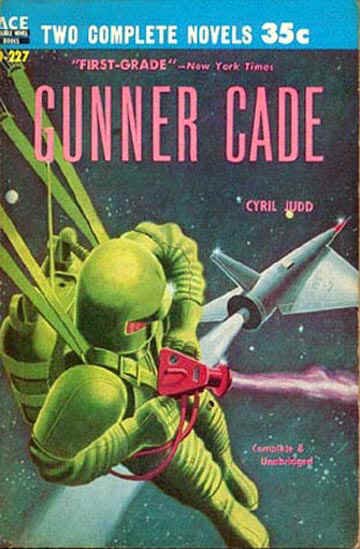

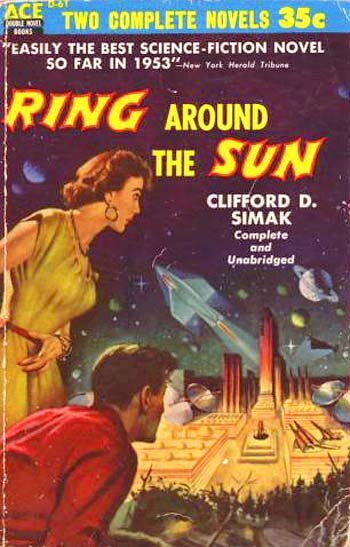

George’s father had enjoyed keeping up with the monthly pulp-fiction magazines – where Burroughs first published and where he continued to debut his stories – in his New York City youth, and he must have recommended Burroughs to George; Leonard Katz, by a coincidence, worked in engineering at North American Aviation, which employed my brother somewhere in ranks of management, and the two knew each other as coworkers. Designing and building the main engine, the J-5, for the Saturn V moon rocket drew their complementary talents into the same project. Two paperback houses, Ace and Ballantine, had recently gambled on reintroducing the Burroughs oeuvre to an American readership that had largely forgotten the once superlatively popular author; so since 1962, commencing with the Ace publication of At the Earth’s Core (1922), cheap editions of the Tarzan stories and the science fiction novels had come available in the bookshops.

Burroughs tended to write stories in multi-volume cycles, knit together by a unifying hero, the best known of whom is Tarzan of the Apes. Before he began mining his ape-man conceit, however, Burroughs had invented the intrepid John Carter of Virginia, a captain of cavalry under General Lee during the Civil War and, after peculiar events while prospecting for gold in Arizona, no less than Warlord of Mars, Prince of the Twin Cities of Helium, Husband of Princess Dejah Thoris, and Honorary Jeddak of Thark – one of the hordes of barbaric Green Men who roam the dead sea bottoms.[2] In the single, universal tongue of Mars, that world’s inhabitants call their planet Barsoom. Curious parties may learn the details of these matters in A Princess of Mars (1910), The Gods of Mars (1912), and The Warlord of Mars (1913), the first three of what eventually became a ten-title series. The last of them, Llana of Gathol, saw publication in book-form as late as 1948. The local bookseller, Martindale’s in Santa Monica on the old Third Street Mall, stocked the Ballantine editions. When I could get my hands on one, I preferred the Ace editions, which featured cover-art by Roy Krenkel, whose sinewy leaping figures in exotic backgrounds belonged to the same hyper-romantic dispensation as Burroughs’ prose. What the NASA-men intently tore down, Burroughs systematically built up, notwithstanding the fact that he lay fifteen or twenty years dead in his grave while the technocrats, to borrow a phrase, contemporaneously scurried about their affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter.

Aficionados of Burroughs rank the original “Barsoom Trilogy” highest among the John Carter sagas; the three stories qualify together as a coherent epic and establish the heroic-crepuscular milieu in which the subsequent installments take their place. Later books of the series, in Linn Carter’s estimation in Master of Adventure (1965), “pot boilers.” “It is to be expected… that the majority of Burroughs’ works do not contain the creative values of the few best.” A passage from Llana, however, rather than one from A Princess or The Gods, best conveys the magic of the Burroughsian fantasy, perhaps because the author himself, at the terminus of his creativity, feels the nostalgic tug of his own long-established myth. John Carter, taking a sojourn from the burden of duty, penetrates unknown regions of Barsoom in his one-man flyer. “It is always a little saddening,” he says in remembering the aerial view, “to look down… upon a dying world.” Yet even in its planetary decadence, rusty old Barsoom displays a multiplicity of fresh wonders. The archeological layers of the global kitchen midden suggest a mystery that the curious might plumb and which they might decipher. The wise will certainly delve, becoming wiser yet, and the lucky ones of them will indeed decipher.

As in some latter-day Marco Polo’s cosmic Cathay-diary, Carter notes:

It was about noon of the third day that I sighted the towers of ancient Horz. The oldest part of the city lies upon the edge of a vast plateau; the newer portions, and they are thousands of years old, are terraced downward into the great gulf, marking the hopeless pursuit of the receding sea upon the shores of which this rich and powerful city once stood. The last poor mean structures of a dying race have either disappeared or are only mouldering ruins now; but the splendid structures of her prime remain at the edge of the plateau, mute but eloquent reminders of her vanished grandeur….

I am always interested in these deserted cities of ancient Mars. Little is known of their inhabitants, other than what can be gathered from the stories told by the carvings which ornament the exteriors of many of their public buildings and the few remaining murals which have withstood the ravages of time and the vandalism of the green hordes which have overrun many of them…. The magnificent edifices were built not for years but for eternities….

What Williamson writes of Wells’ scientific romances – that “I fondly recall the thrill of widened horizons they gave me in my own teens, when I first found them reprinted in the gray pulp pages of Hugo Gernsback’s then-new Amazing Stories” – applies equally to Burroughs, making allowance for Wells’ wider novelistic range and somewhat more literary character. I like Williamson’s phrase, “widened horizons.” In the Burroughsian passage above, for example, one confronts in its essential form a typical quality of science fiction. The plot in a science fiction story frequently turns on the discovery that time possesses a hitherto unsuspected depth and that sophisticated civilizations existed well before the present one had emerged even in its earliest stage. Plato used this conceit prototypically in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias, where the Atlantis-story makes its debut; that island-nation vanished beneath the waves, Plato’s narrator says, nine thousand years before the heyday of Athens under the regime of the Pericles. “You remember only one deluge,” the Egyptian priest instructs his Greek visitor loftily, “though there have been many.”

The invocation of deep time serves to shock readers out of their parochialism and complacency. The remains of Barsoomian Horz in Llana remind us of the planet’s antiquity, of its layers of succeeding civilizations and polities, and of the struggle of its people against the shrinking resources of their world. The phrase “hopeless pursuit of the receding sea” tells of the heroic determination that takes up the fight not only against implacable natural processes but also against the tendency of people to succumb in advance to the mere suspicion of a defeat. The past is not, therefore, the worthless detritus of empty days that people might as well forget; it is a saga that they should remember, on whose lesson a community may sustain itself in its current hardships.

“The magnificent edifices” of Horz in its prime, Burroughs writes, “were built not for years but for eternities.” The paltry later constructions have already rotted away into the encroaching sands. When one lives in a place as bereft of history as Southern California one imagines the archeological strata; in so doing one compensates spiritually for an actual deficiency in the surroundings. Burroughs lived in the San Fernando Valley, which, while lovely in his day, could not boast of much in the way of history, and of little more today. The name of the San Fernando Valley stands as synonymous with postwar suburban shallowness. In remarking on those fantastic edifices built for eternity, Burroughs might well be aiming an oblique criticism at the cheap construction that prevailed in the Valley in the crass boom-time after World War Two, as along Ventura Boulevard. During this phase of aggressive real-estate development, the Burroughs ranch, much subdivided, became the bedroom community of Tarzana, located not far from Granada Hills, and lying just over the mountains from the twenty-seven-mile-long Malibu shoreline. A cheap, unimaginative architecture prevailed there, too, which sprouted up in the same period, blocking the view of the ocean.

Burroughs’ Barsoom, richly imagined, differs but little in its stratified ancientness from Wells’ implied, although not fully realized, Mars of The War of the Worlds because both begin in the fin-de-siècle vision of the fourth planet from the sun. In the Conclusion of Mars (1894), Lowell writes, “Mars being thus old himself, we know that evolution on his surface must be similarly advanced.” Later he adds: “Quite possibly [the] Martian folk are possessed of inventions of which we have not dreamed, and with them electrophones and kinetoscopes are things of a bygone past, preserved with veneration in museums as relics of the clumsy contrivances of the simple childhood of the race. Certainly what we see hints at the existence of beings who are in advance of, not behind, us in the journey of life.”

Lowell, who saw canals and oases on Ares’ dusky sphere, was a Transcendentalist, after Emerson, while Wells was a Darwinian and a materialist; Burroughs shows elements both of a materialist’s unsentimental skepticism and of a Theosophist’s baroque credulity. This explains their differences with respect to the Martians. All three agree, despite their differences on the other matter, that, where the Martians abide in farsighted ancientness, the human race slumbers in the cradle of its infancy and cannot yet have attained wisdom.

IV

Sensitive interpreters will detect a subtle but pervasive epistemological theme in Wells’ The War of the Worlds. In flight from Horsell Common, where the Martians, emerging from their pit, have unlimbered their heat-ray, Wells’ narrator encounters a trio of young people who not only know nothing of the calamity but also laugh off the notion that anything untoward might alter their existence. The narrator asks, “Haven’t you heard of the men from Mars?” “Quite enough,” says a young woman among them, whereupon “all three of them laughed.” The laughter signifies their perfect complacency. Says the narrator, “You’ll hear more yet.” At Shepperton, on the day after the Martians have begun to move in earnest, “the idea people seemed to have… was that the Martians were simply formidable human beings.” In the Epilogue of the romance, the story-teller remarks that “we have learned now that we cannot regard this planet as being fenced in and a secure abiding place for Man.” Knowledge, which never serves man, divides men into the two great groups of the witting and the unwitting or of the satisfied and the unquiet. Wells’ narrator describes himself as tending habitually to “the strangest sense of detachment from myself and world about me,” which, in such a mood, he watches “from outside, from somewhere inconceivably remote, out of time, out of space, out of the stress and tragedy of it all.” He is himself, so to speak, a Martian, in that he makes objective scrutiny of the situation, if not his modus operandi, at least his invariable opening move. In fact, all his struggles have the Homeric-nostalgic aim of reuniting him with his beloved wife. Wells provides the narrator’s foil in The War in the form of the whining Curate, who, interpreting the alien onslaught as the Biblical Day of Judgment, succumbs to paralytic fatalism. Unable to square himself with reality, he falls victim to the Martians, nearly taking the narrator with him.

In Burroughs, too, one finds a sorting out of truth from falsehood, as in The Gods of Mars (1912) and The Mastermind of Mars (1926), where the hero in each case must, in the course of his ordeal, throw over the empty idols of a sacrificial cult and liberate the people from superstition. But I needed Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles to present me with the rhetorical trope (a word I try to use here precisely rather than profligately) that crystallized and so gave form to the faith with which I invested the genre. The sentence that knocked me flat occurs in the second item of Bradbury’s twenty-six-item episodic forecast of human, all-too-human affairs commencing in January 1999 and concluding in October 2026; the story, called “Ylla” after its golden-eyed brown-skinned lady-Martian protagonist, concerns the arrival on that delicate globe of the First Expedition from earth and its unexpected and violent fate. Let me first offer a few of the contextual details, for the character of Bradbury’s imagery, which exerted a strong pull on me, justifies some exposition. He visualizes his Mars intensely, with tactile vivacity, lending it a kind of palpable, physiognomic truth. I will quote the catalyzing period from “Ylla” at the end of the paragraph after the next one.

Ylla and her husband Yll abide with one another testily “in a house of crystal pillars… by the edge of an empty sea,” an imaginary locale reminiscent both of Burroughsian Horz and of Venice, California, the seaside suburb of Los Angeles, decaying from its original upper-middle-class primness into incipient slum-like desuetude, where Bradbury lived and wrote in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The “hot wind” of Bradbury’s Mars resembles the notorious Santa Ana winds of Southern California, the ones that spark and then drive the hillside conflagrations that my father became expert at fighting as a captain and then as a battalion chief of the City Fire Department in the same decade. As Bradbury first reveals him, Yll sits alone in the library of his house, “reading from a metal book with raised hieroglyphs over which he brushed his hand, as one might play a harp.” The pages speak as Yll strums, reciting legends “of when the sea was red steam on the shore and ancient men had carried clouds of metal insects and electric spiders into battle.” The allusion to ancientness is apt, for Yll’s heroic lays bear a distinct, a directly genealogical relation to those “stories told by the carvings” of age-old Horz in Burroughs’ Llana. In the oceanic “red steam on the shore” Bradbury appears in a mood of self-reference, for his Venusian novella Lorelei of the Red Mist (1944), co-written with Leigh Brackett (1915 – 1978), sets its action against a similar ruddy backdrop.

In the Chronicles story, the husband and wife have grown apart, Ylla yielding herself up to erotic daydreams and Yll to his chansons de geste. The anomie of their marriage serves as an indicator of profound dislocations in Martian culture, which Bradbury represents as, in many ways, degenerate. Ylla reports to Yll a dream she has had about a tall blue-eyed man, arriving on Mars from the third planet in a shining metal conveyance, a man who meets and woos her. Bradbury’s Martians suffer from morbid, uncontrollable telepathy: Ylla’s dreams forecast the actual, imminent advent of astronaut-explorer Nathaniel York and his co-pilot Bert from earth. Quoth the husband, a jealous fellow who seeks any opportunity to belittle an estranged wife more vital and acute than he: “The third planet is incapable of supporting life… our scientists have said there’s far too much oxygen in the atmosphere.”

In 1907, Alfred Russell Wallace (1823 – 1913) published his pamphlet – Is Mars Habitable? This was in response to Mars and Its Canals (1906) by Lowell, which became a cause célèbre among a large popular readership. Wallace, co-discoverer with Charles Darwin of the idea of biological evolution through random selection and the survival of the fittest, anticipated the stone hearts of the Mariner 4 lab-coats by saying, in so many words, what Yll says in Bradbury’s jewel-like chronicle. Bradbury had certainly read Lowell and he had probably read Wallace. Whatever the case, he knew well what an increasingly authoritative scientism had done, under its killjoy imperative, with the variegated living orbs of Nineteenth Century astronomical speculation. He interpreted the scientistic nay saying – accurately – as the symptom of a spiritual malaise, a loss of the capacity to believe, a loss of pneumatic orientation in a universe deliberately denuded of significance. While I hardly qualified as a bright seventh-grader, the celestial assizes must have acknowledged me as one who had steeped himself steadily for some years in books, often a bit over his head, acquiring a respectable lore along the way. I could therefore recognize Yll as a type wedded to a view. Many of my teachers belonged to this type and espoused the same view; they were moral policeman dedicated to rooting out what struck them as eccentric and, I suppose, nasty ideas. In Ether Wave, the ditto mastered “science fiction magazine” that my friends and I produced on school equipment at this time, George Katz had written: “There are people who wouldn’t be caught dead reading what they count as ‘trashy fantasy.’”

On the other hand, George wrote, “there are people who make sure that at least one book out of ten that they read is science fiction,” a marvelous statement for its assumption that reading books by the ten-count is a perfectly normal endeavor. The fading copy of Ether Wave is noteworthy for its grammatical integrity, which was not the result of our teacher-supervisor, Leonard Vincent, rewriting any of the material.[3]